The world known as Middle Earth that was created by the great author and professor J.R.R. Tolkien has reached millions of people ever since the publishing of his first book The Hobbit. However, something you might not know about the world of J.R.R. Tolkien is that he was writing about it as long ago as 1917, but even more so, he was creating the languages of Middle Earth since 1910. The two most well-known languages that he created are the Elvish languages of Quenya and Sindarin, which both use the writing system Tengwar. While Tolkien only used Tengwar for those two languages, he did speculate in the appendices that it could be used for other languages – and he was right. After the popularity of his books and his death in 1973, fans started figuring out how to use the Tengwar alphabet and tweak it so that it could fit with the English lexicon. Today, Tengwar modes have been created by fans all over the world for all different languages and I personally have learned it, so today, I’m going to teach you the basics of how to write in Tengwar.

The first thing to note is the definition of a “mode.” A mode is simply a way of rearranging letters in a different alphabet to fit those in another. Today, countless modes have been created by the fans, but the most used one is the English mode. There are two versions of English mode Tengwar, orthographic and phonetic. For the sake of simplicity, I’ll use the orthographic version, which is based primarily off of how words in the English language are spelled.

In the Tengwar alphabet, there are 24 primary letters, which are all consonants, as well as 16 additional letters. In English Mode Tengwar, you only use 34 of these letters, which are called Tengwa. Each of these letters are divided into groups of four, and are placed into 10 tyellë, which represent sounds made in different parts of the mouth. These letters (primary and additional) are; Tinco (t), Parma (p), Calma (ch), Quessë (c/k), Ando (d), Umbar (b), Anga (j), Ungwë (g), Thúlë (th), Formen (f), Harma (sh, though can also be used for s as in “sugar”), Hwesta (CH), Anto (TH), Ampa (v), Anca (zh though used for s/z in words like “treasure, azul”), Unquë (gh), Númen (n), Malta (m), Ñwalme (ng), Órë (r), Vala (w), Anna (y), Rómen (R), Lambë (L), Silmë (s that sounds like an s), Silmë Nuquerna (c that sounds like an s), Ázë (z), Hyarmen (h), Hwesta Sindarinwa (wh as in “what”), Yanta (-e), Anna for consonant y, Sa-rincë (x) and Ossë (-a). In this list, you might’ve noticed that there are Tengwa that represent the same consonants or consonant combinations such as Órë and Rómen or Thúlë and Anto. Why is that? Even though this is the orthographic mode, Tengwar is still a very phonetic language that is also very malleable to fit with different dialects. Thúlë is representative of a voiceless “th” that is found in words such as “both” or “nothing.” Anto is a voiced “th” found in words like “that” or “mother.” These Tengwa can be used however you want depending on what dialect you speak. The same goes for Órë and Rómen. While most people like using these two in the same way Quenya does (where Rómen is placed before a vowel (unless that vowel is a silent e); and Órë is placed after vowels), if you speak a dialect that drops the r’s, then Órë can be used for every r. However, there are exceptions to every rule. In Tengwar, the letters Quessë and Hwesta cannot be used interchangeably. Quessë represents a “ch” sound found in a word like “church” while Hwesta makes the “ch” sound found in “loch.” These two letters cannot be interchanged. In addition, Quessë’s telco (the long stem) can be extended to create a “ch” that has a “k” sound.

Alongside the Tengwa are symbols called Tehtar. The first type of Tehtar is Vowel Tehtar and are placed on the consonant Tengwa that comes after the vowel. I will show these at the back of this paper. In English Mode Tengwar, the vowels are read from top to back. An exception to this rule is the Tehtar for silent e which is always placed under the consonant and read from left to right. If there is no consonant to carry the Tehtar, you can use either a Telco or Ára vowel carrier. The difference between these two is that the Telco is smaller and looks more like the stem of a letter “i.” Meanwhile, Ára is longer and looks more like a letter “j.” Telco is only to be used when there isn’t much stress being put on a vowel or when it makes a short sound. Ára is for long sounds where the vowel says its name like in the word “a.” When you have a diagraph (combination of two vowels), use Ossë for diagraphs that end in “-a”, Yanta for diagraphs that end in “-e”, Anna for diagraphs that end in “y/i”, and Vala for diagraphs that end in “u/w”. In addition to vowel Tehtar, there are consonant doublers, nasal-tehta, S-tehta and W-tehta. Consonant doublers go under a consonant and can be used on any consonant while nasal-tehta can only go over Malta, Númen, and Ando. An exception to this is if you have an “ng” sound where the g can be heard (such as in “finger”), in which case, you put the nasal-tehta over Ungwë and extend the telco downwards. W-tehta looks like the Spanish “tilde” and is used when there is a “qu” combination. The reason why is because, in Tengwar, there is no letter for q, therefore anything written with “qu” is replaced with “kw.” Finally, the S-tehta is the simplest one of the bunch and goes at the end of a word that ends in s. If a word ends with “es”, you put an e-vowel-tehta over the s.

Lastly, punctuation. Tolkien was very inconsistent with his punctuation in his writings, but the best fans can figure is fairly simple. In Tengwar, commas are represented by a single dot (.), while periods are represented by what looks like a colon (:). However, this rule is broken when a sentence comes to the end of a paragraph. Instead of using two dots you use three (though in some forms four are used; use what you prefer) and at the end of an important document, a symbol that looks like this is used (:~). It does not have to look exactly like that, but it is the most general version. For important words that must be capitalized, red ink is used, but this is only done in important documents or for the names of important people.

English Mode Tengwar can be a hard alphabet to learn how to write, but with a bit of practice, I think you will be able to understand it and soon be writing in it as though it was second nature. Remember to practice, practice, practice. Write your notes or diary in Tengwar. Next time you go shopping, write your list in this beautiful Elven alphabet. This will increase your ability to write it correctly and understand what you have written. If you need additional help, I suggest buying Write English in Tengwar, by Fionna Jallings. That workbook can help you understand some of the things that weren’t covered in this paper and is pretty cheap. For additional help learning Tengwar, I also suggest going to some fan forums such as Tengwar Translator which can be easily found on Google. So, what are you waiting for? Go forth and write like an Elf.

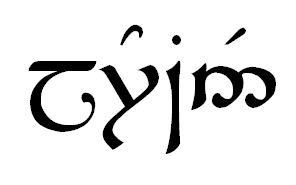

Until next time,

M.J.

Discover more from The Tanuki Corner

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

nice article. ill leave my thoughts…

Thanks for reading , Love The Blog !!

Please check out my new blog for all things Dog – http://www.pomeranianpuppies.uk

LikeLike